#Open call article 3: This blog is part of an ‘open call’ to researchers, students or anyone interested in ethnobotany to write an article for the SEB student blog.

Here’s the third article from this call by Garrett Cessna

Acknowledgement: Thanks to a grant from the Tinker Foundation to support my work on urban ethnobotany, and the support of CLACS at NYU, I was able to spend the month of June 2025 in the cities of Cusco and Lima, Peru researching traditional knowledge (TK) for medicinal plants. What I had originally imagined would be a month of conducting interviews, ethnographic work, visiting museums, seeing archives and collections of print materials, and also visiting open air herbal markets–quickly turned into a month-long immersive experience talking to as many people and organizations as I could to answer my research questions. This was my first time receiving grant money to conduct fieldwork, and I had only been out of the country a handful of times before that, so I was completely ecstatic about finally being able to see and work in the Andes in person.

As a West Virginian and Appalachian, I avoided altitude sickness upon my arrival to Cusco–thinking nothing about the city’s vertical k’ikullus (narrow streets from Inkan times) and skyward staircases. But after about a week, I found myself sick with the flu and confined to the small bedroom that I had rented for the month. Thinking about what little groceries I was able to buy at the mini-mercado (mini market) next door before getting sick, I remembered the pre-packaged mate de coca that I had recognized on the market vendor’s store shelf. I took a cold medicine tablet that I bought from the botica (pharmacy) that morning, and then made myself a cup of the packaged mix, thinking it would help to soothe my sore throat.

Image 1. Two packets of pre-ground, and pre-packaged mate de coca. The product is prepared by steeping the contents of the bag in hot water for 5-10 minutes, or until the water turns a deep greenish-brown color, and is consumed hot. Image author’s own.

Staring at the greenish brown mixture in front of me, I remember being unsure of what exactly to expect to happen. Growing up in the U.S., I had always been warned of coca–the plant from which cocaine is derived–as a dangerous drug that could cause extreme bouts of energy, uncontrollable fits of hyperactivity, or even heart failure. However I had also heard of and studied the plant in college, and later grad school, as a plant with a millenium of use as medicine in the Andes. Both thoughts sat heavily on my mind as I began to sip from my mug. To my surprise, what I experienced that day was neither hyperactivity, nor heart failure, but a slight stimulating effect milder than a cup of coffee. After about two days of rest and drinking mate de coca, I suddenly found myself revived. My flu was gone, and my energy had returned!

Image 2. Mate de coca is traditionally consumed by placing a handful of coca leaves (the contents of the green bag) into a mate, or gourd (the brown, wooden mug in the center of the photo), and drinking the steeped contents through a bombilla (the metal straw within the gourd). The bombilla has a filter at the end so as not to directly consume or swallow any whole coca leaves. Image author’s own.

Throughout the following weeks in the Andes, I remained curious about the uses for mate de coca, the different ways it could be prepared and consumed, and how Andean peoples were using the infusion as medicine. Out of curiosity, and after a few conversations with various cusqueños (residents of Cusco), I had come to understand that mate de coca could be taken for fatigue, headache, altitude sickness, cold and flu systems, and some people who I had asked even recommended its daily use for more chronic health issues like arthritis and cancer symptoms. I quickly came to realize that the plant that had helped me recover from a full blown flu so rapidly was an Andean cure-all. During some of my ethnographic work at a market nearby, I spotted a traditional Andean mate, or gourd, that came with its own bombilla–all for the equivalent of $10 USD. Needless to say, it was an offer I just couldn’t pass up. I continued to drink coca tea during my time in Peru, now using a traditional mate and bombilla to consume the coca that I had bought in the same market that I had visited. I had quickly come around to the plant after realizing my understandings of it were deeply distorted by neocolonial, narcotrafficker narratives surrounding coca–a plant which is revered for its medicinal and soothing qualities throughout the Andes today.

Image 3. Photo of a mature coca (Erythroxylum novogranatense) plant at the Centro Nacional de Salud Intercultural’s Jardín Botánico de Plantas Medicinales in Lima, Peru. Image author’s own.

There are few plants in Latin America with quite the same social importance, ties to colonization, and the emergence of modern labor systems as the coca plant. Coca is easily one of the world’s most recognizable, cultivated, and utilized plants native to Andean South America–yet remains one of the most demonized on a global scale. Coca has been cultivated for thousands of years by Indigenous peoples in the Andes beginning in pre-Columbian times. In 2025, and from the perspective of the modern era more generally, it’s almost impossible to imagine life in the Andes without it.

Image 4. Packaged coca (Erythroxylum) and muña (Minthostachys mollis) being sold at the Mercado Central de San Pedro in Cusco, Peru. Andean city-dwellers are more likely to obtain medicinal plants from open-air herbal markets than to cultivate their own ethnobotanicals, as space and land resources are limiting factors within metropolitan centers. Image author’s own.

Part of what makes coca so unique is that it differs from many plants with psychotropic effects in many ways. To begin, rather than referring to a single species–how many people might think of the plant–the common name coca can actually refer to a number of plants within the genus Erythroxylum. The two most common species include Erythroxylum novogranatense and Erythroxylum coca, but varieties exist within both. It’s generally agreed upon by biologists today that two to four species of the plant exist; however, it remains hard to morphologically differentiate these species in the field. Oftentimes, what differentiates one species of coca from another is its community or region responsible for its cultivation–with Erythroxylum novogranatense dominating in Colombia and the Pacific Coast, and Erythroxylum coca being found mainly in the Western Andes and Amazon. In Cusco, where I first tasted mate de coca, both species are used interchangeably in plant medicine, market sale (see image 3), and industrial mate production.

Coca’s effects are primarily stimulating, speeding up the central nervous system and triggering circulation in the body to increase blood flow–creating a physiological sensation of a slight to mild “energy boost” in its user. For this very reason, the coca leaf was given to Andean laborers first in the Inka civilization for use in the mitayo labor system, and then under Spanish colonialism in Andean silver mines; in both circumstances, coca served as a means of energizing the workforce and boosting production. However by and large, mitayo laborers and Andean miners were not consuming coca as a mate, but rather by chewing leaves from k’intus (leaf bundles) laced with trace amounts of liquified llipt’a (an ash mixture made from lime, quinoa, corn husk, and/or stevia). And when consuming coca as so, the ash mixture contributes an organic molecule, ecgonine, to the consumer (in addition to the stimulating effects of coca). In turn, ecgonine allows for increased carbohydrate uptake from diet while also suppressing appetite, meaning that more nutrients could be taken up from less food provided to workers while simultaneously increasing their productivity–creating the perfect recipe for labor exploitation and forever altering labor systems in the Andean silver mining industry. Thus, coca use and consumption in Peru’s colonial period justified Andean poverty, labor exploitation, and unsafe working conditions within and outside of silver mines for centuries to come.

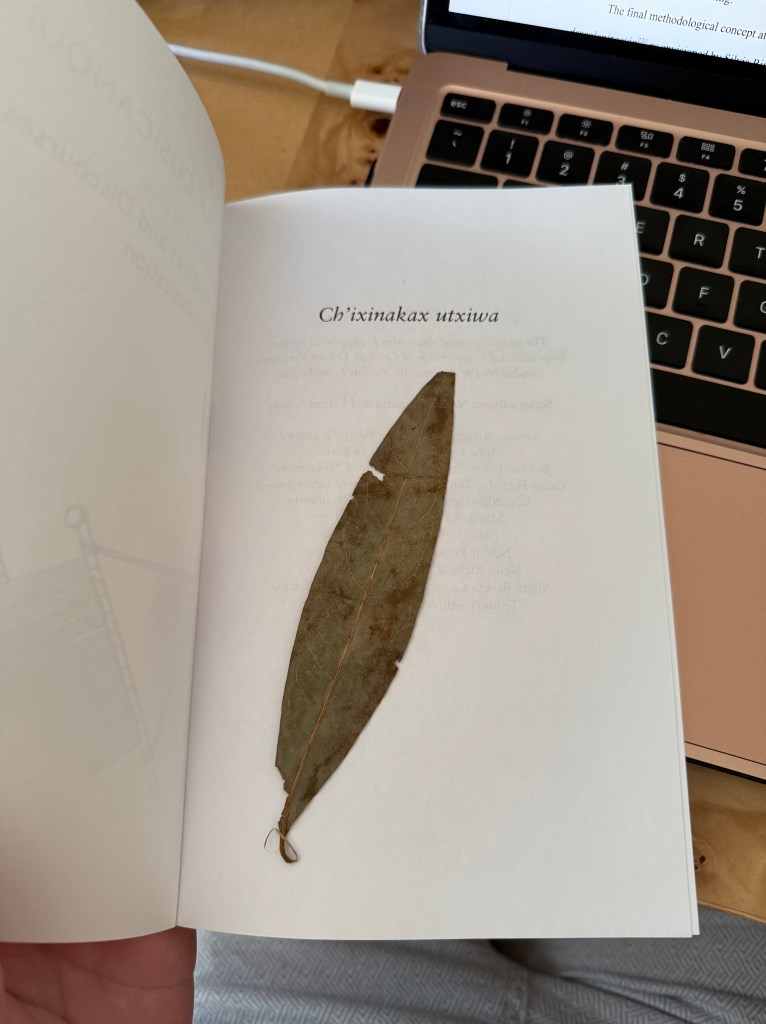

Image 5. A pressed coca leaf from my fieldwork in Cusco, Peru (June 2025). The book in the background of this photo is Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: On Practices and Discourses of Decolonization (2020) by Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui. Image author’s own.

These are just a few examples of the long and complicated history of coca use in the Andes, all of which continue to fascinate me and form an integral part of my graduate research. That same fascination which led me to buy my own mate and continue consuming the infusion long after I had recovered from my flu had also led me to press a leaf of the plant in a book that I had taken along with me to Peru (see image 4). Whether it was to remember the trip in souvenir fashion, or maybe even to memorialize my experience with the coca plant in 2025, my opinion on the plant was put into perspective in undeniable ways that June. On my flight returning to the U.S. from Peru, I began to think about my reckoning with coca. After returning to the US, where the coca plant and its derivatives are all illegal and considered as a Schedule II drug, I was left with the unshakable feeling that the fear of coca instilled into U.S. citizens through criminalization is a complete refusal to recognize the plant’s power as a medicine. The same power that the Inka saw in the plant, and that the Spanish recognized early on in their colonial project in South America, is exactly what the Global North fears most about the plant. And despite this fear, the power in the plant–and its potential to influence our culture and social world–remains.

Image 6. Myself, drinking mate de coca for the taste at the end of June 2025 in Lima, Peru, about three weeks after recovering from my flu in Cusco and having the beverage for the first time. Image author’s own.

Author bio: Garrett Cessna (he/él/ele) is an ethnobotanist, Latin Americanist, and museum professional who holds a B.A. in Biology and Spanish from West Virginia University. Garrett is a second year MA student in Latin American and Caribbean Studies, with a concentration in Museum Studies, at New York University. He is a FLAS Fellow for Quechua, and has experience at the American Museum of Natural History and the Art Museum of West Virginia University. Garrett’s research interests include (but are not limited to): the plants of Latin American colonialism, traditional knowledge [TK] systems for medicinal plants, Andean plant medicine, and coca culture (Erythroxylum genus). Garrett’s research is interdisciplinary, strives to understand plant use from various perspectives, and utilizes anticolonial and decolonial methodologies. Email: cessnagarrett1@gmail.com

Open call: If you also want to contribute an article to the SEB student blog, go ahead and send your plant story to Nishanth Gurav, email: gurav@ftz.czu.cz

Minimum: 500 words, maximum: 2000 words (including pictures) including title and article

Leave a comment